COVID-19 – APPLYING FIVE SAFETY LENSES TO PLAN FOR A SECOND WAVE

In 2013, Charles Vincent, Susan Burnett and I published The Measurement and Monitoring of Safety Framework (Vincent, Burnett and Carthey, 2013; The Health Foundation, 2014). Given that a second wave of COVID-19 is a real possibility, I have adapted the Framework and applied its Five Lenses of Safety, (past harm, reliability, sensitivity to operations, anticipation and preparedness and integration & learning), to illustrate some of the safety data, metrics and soft intelligence, health and social care organisations must seek out and integrate when planning for future outbreaks:

The Measurement and Monitoring of Safety Framework

Past harm

Looking through the past harm lens, (our rear view mirror), we need to reflect and learn from what we now know about the types of harms suffered by patients and staff, and what we can learn from them. Questions health and social care organisations might ask when looking through the past harm lens are: How many hospital or care home acquired COVID-19 cases did we have? What gaps in our systems and processes contributed to them? What can we learn from incident reporting, complaints, and claims data? What is our excess mortality rate? What worked well to prevent or recover harms (i.e. Safety II learning including administering dexamethasone to ventilated patients)?

Past harm is not just about learning from physical harm to patients, staff, residents, and those receiving treatment in their own home, for example, from hospital or care home acquired COVID-19. It is also about reflecting on other types of harm including, for example, dehumanisation and psychological harm: COVID-19 patients who are hospitalised are (necessarily) separated from their loved ones to reduce the spread of infection. What can we learn about how we supported patients, their loved ones, and staff through that enforced separation? Did we maximise the use of IT technologies and social media to ensure contact was maintained? What did we do well to support both patients, their loved ones, and staff? How did we adapt our ways of working to prevent dehumanisation and psychological harm to both patients and staff (i.e. Safety II learning)?

Reliability

The reliability lens enables us to reflect on how reliably our clinical and non-clinical systems, processes and pathways worked. Looking through the reliability lens, are there lessons from how we reconfigured services to manage the pandemic which had unintended consequences for patient and staff experience, and efficiency? Is there a better way to manage service reconfigurations in the future? Are staff support services working reliably, i.e. what are the waiting times for staff to access support and counselling services? How well is the PPE supply chain working? Are there inefficiencies in the turnaround times for test results to become available and if so, how might we resolve these? How might we improve the reliability of both clinical and non-clinical systems based as we plan for a second wave?

Observing, listening, and perceiving (sensitivity to operations)

The third lens of safety, sensitivity to operations, is simply how health and social care organisations tune into safety risks by observing, listening, and perceiving. Are staff wearing PPE wearing it for long periods of time and if so, how has that affected their performance? Have staff fed back that they or their colleagues get dehydrated whilst working in PPE? Do observations of behaviour in communal areas, during rest breaks and in hospital lifts highlight environmental and points during a shift where it is more challenging to follow social distancing rules? Are our conversations with frontline staff giving us warning signs that staff are burnt out, tired, stressed, and traumatised? Is PPE readily available, including for non-clinical staff like cleaners, receptionists, catering staff etc.? The value of soft safety intelligence from what one sees, hears and perceives cannot be under-estimated: It is often the best indicator of how behaviour and practice in the ‘real world’ has drifted from the ‘world as imagined’ in policies, procedures and guidelines. As such, it must be at the heart of second wave planning.

Anticipation & preparedness

The ‘anticipation and preparedness’ lens involves asking the question, ‘Will care be safe in the future?’ From a COVID-19 perspective, the challenge for health and social care organisations are that much of the data which supports anticipation and preparedness is not generated by the organisation itself: Keeping abreast of media and social media reports, and research articles (both nationally and internationally) is vital. For COVID-19, media and social media are useful tools which may provide early warning signs that the general public’s behaviour could be increasing risk. For example, mass gatherings in the local community or social media reports describing public non-compliance with social distancing rules in supermarkets, at work etc. Tuning into public behaviour in the local community is especially important. So, is knowing your local business demographic, for example, what businesses exist in your local community where following social distancing is challenging for the workforce? What risks does your local business demographic introduce?

Anticipation and preparedness also involve asking different questions of existing data sets. For example, do annual leave rates indicate staff who are integral to the organisation’s response to COVID-19 (both frontline and non-clinical staff) have not taken their allocated leave? Has staff turnover increased and, if so, what are the implications of increased vacancy rates on the safe provision of future care? What does our occupational health and staff support services data tell us about how our workforce is feeling and coping? Are risk assessment and burnout tools being used and if so, what is that data telling us? Are we maximising the value of staff risk assessment data or has it turned into a ‘tick box’ exercise?

Integration & Learning

Finally, second wave planning involves integrating and learning from the plethora of hard data and soft safety intelligence health and social care organisations have gathered across the other four lenses (past harm, reliability, sensitivity to operations and anticipation & preparedness). The complexity of the integration challenge for COVID-19 is exacerbated because the world is still on a learning curve. Health and social care organisations are also working in a context where guidelines and policies change in line with new research evidence, and where new causes of risk are still being identified. What is important for both integration and learning is to look beyond our own organisational or health economy boundaries, and to seek out what has worked well and what has not (both nationally and internationally). We also need rapid feedback mechanisms in place to ensure lessons are shared effectively. Finally, it is vitally important to give equal weight to soft safety intelligence gathered from what we see, hear and perceive, and to integrate staff, relative and patient experience data alongside hard metrics (i.e. dashboard data on infection rates, mortality and morbidity rates etc..).

Lessons learnt Wave 2 planning flyer

Posted on June 19, 2020 : 6:12 am Comments (0)

Filed under news

Seismic shifts or gradual maturity? Safety Measurement and Monitoring in Healthcare

How mature is your organisation’s approach to measuring and monitoring safety? Is your Board over-confident it ‘has safety sorted’ and doing nothing to evolve its approach? Are you entrenched in ticking the box to prove the organisation is safe to external regulators? Or is your organisation continuously innovating to improve its safety metrics and methods?

The Safety Measurement and Monitoring Matrix (SaMMM), (see Figure 1), has been developed to support healthcare organisations self-reflect on their safety measurement culture. Based on Robert Westrum’s theory of different organisational personality types (1992), and the approach taken to develop a previous tool, the Manchester Patient Safety Framework (Kirk, Parker et al., 1997), SaMMM maps out what different organisational personalities look like on each of the Health Foundation’s Measurement and Monitoring of Safety Framework dimensions (Vincent, Burnett and Carthey, 2013). Those dimensions are:

i. Past harm

ii. Reliability

iii.Sensitivity to operations

iv. Anticipation and preparedness and

v. Learning and integration

SaMMM is currently being tested in workshops with healthcare teams. Initial feedback has shown SaMMM can be used to stimulate conversations and self-reflection. In a recent workshop, one healthcare professional commented how it takes a ‘seismic shift’ for an organisation to mature from the bureaucratic personality type to a more proactive level of maturity. Evolving our measurement culture may not be a gradual evolution – it may require a fundamental re-focusing of energy and resource, prompted by a change in leadership or leaders completely re-thinking their vision for safety.

Another participant commented how the Trust Board in his organisation believes they are proactive and will not be told otherwise. This has paralysed attempts to evolve the safety measurement culture in specific teams and divisions. Thus SaMMM highlights the gulf that sometimes exists between senior managers and frontline staff about how evolved their approach is.

Please feel free to download and use SaMMM [Download here…] in your organisation or team. I would be interested in hearing your feedback and how you have used the tool, so please drop me an email at jane@janecarthey.com

Posted on February 22, 2016 : 1:00 pm Comments (0)

Filed under news

THE GENERIC SURGICAL NEVER EVENT FISHBONE DIAGRAM

The generic surgical never event fishbone was developed by Dr Jane Carthey. It is based on the findings from previous never event investigations and published literature on the underlying causes of surgical never events.

The fishbone diagram captures the team, organisational & strategic, task, patient, communication, education & training, equipment, working condition and individual staff factors that increase the risk of surgical never events.

How can I use it?

The generic surgical never event fishbone diagram can be used in many ways:

- As an educational tool – use it as a platform to have conversations with theatre teams, managers and NHS Boards about the causes of surgical never events.

- During incident investigations – incident investigation leads can use it to check their investigation has identified human factors issues like team psychological safety, fixation and workload.

- Conversations with NHS Boards and CCG leads – to explain the multi-factorial nature of surgical never events and in particular, the systems and cultural issues that need to be addressed to prevent them.

- As a proactive tool – theatre teams can use it during debriefs and audit days to appraise the level of risk in a given operating theatre, and to develop solutions to resolve emerging safety threats.

Who can use it?

The generic surgical never event fishbone diagram was developed to share with healthcare organisations in the spirit of learning and improvement. Please cite Dr Carthey as the author and feel free to share it with anyone who may find it a useful tool.

Providing feedback on how you use it

Please contact Dr Jane Carthey (jane@janecarthey.com) with any feedback or examples of how you have used the generic surgical never event fishbone diagram. [Download PDF here or click on thumbnail below]

Posted on November 13, 2015 : 6:10 am Comments (0)

Filed under news

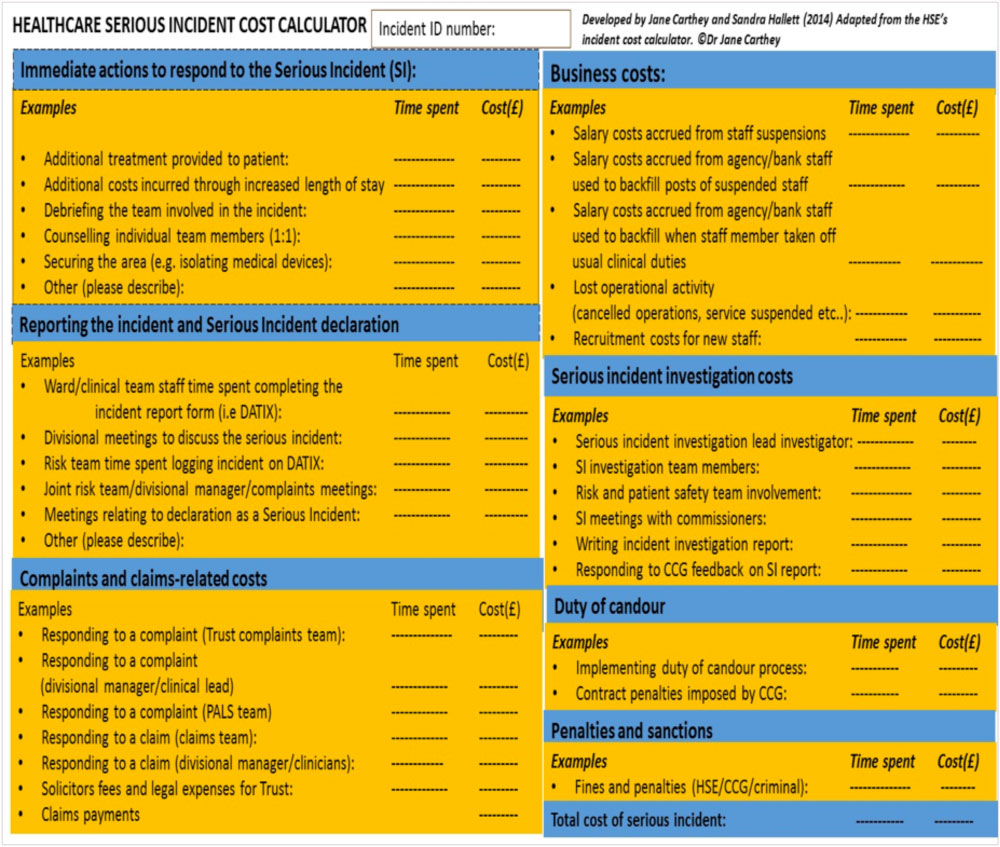

Serious incidents in healthcare: What’s the true cost?

How much does the NHS spend each year managing and responding to serious incidents?

Although several studies have tried to quantify the cost of ‘adverse events’ in healthcare, the true costs remain unknown. To understand the ‘true cost’ of serious incidents we need to consider:

- The cost of additional treatment for the affected patient.

- The opportunity costs that accrue from reporting and managing incidents, claims and complaints

- Business costs that accrue when, for example, healthcare staff are suspended.

- Costs resulting from implementing the duty of candour process, and

- Penalties and sanctions imposed

In other industries, the HSE’s Incident Cost Calculator is used to quantify the true costs of incidents. Inspired by this tool, I developed the Healthcare Serious Incident Cost Calculator:

The tool aims to focus senior manager’s attention on the financial implications of not investing in patient safety. In a climate driven by finance and efficiency savings, we need tools like the Healthcare Serious Incident Cost Calculator to ensure patient safety does not become a secondary goal.

What’s the true cost of serious incidents in healthcare? We don’t know, Maybe by applying the Healthcare Serious Incident Cost Calculator we can begin to understand?

Posted on June 14, 2015 : 4:55 am Comments (0)

Filed under news

Distancing, Denial and Assumptions: Saying sorry when things so wrong

DISTANCING AND DENIAL

How would you react if you were involved in an incident that harmed a patient?

How would you react if you were involved in an incident that harmed a patient?

- Would you be concerned about the potential legal and disciplinary consequences?

- Would you worry about what your peers were thinking and saying?

- Would you feel disbelief and shock?

- Would you try to blame someone else in the team for what had happened?

- Would you feel unsure about what action to take next?

If you have answered ‘yes’ to any of these five questions then you, like the majority of healthcare professionals, are susceptible to distancing and denial in the immediate aftermath of an incident. Now consider the following scenario:

How would expect the healthcare team treating your parents/child/self to behave if an incident occurred during their or your treatment?

- Would you want to know what could be done to repair the harm caused?

- Would you expect a sincere apology and an explanation?

- Would you want reassurance and support?

- Would you expect the healthcare team involved to investigate and learn lessons?

- Would you want reassurance that the healthcare organisation would prevent another family going through a similar experience?

The chances are you answered ‘yes’ to one or more of these questions.

And herein lies the complexity of offering sincere, honest apologies and explanations when things go wrong: One the one side, we have healthcare professionals who become so paralysed by shock, fear and disbelief after an incident that their initial reaction is distancing and denial. On the other, we have patients and carers who desperately need to understand what has gone wrong, why and what is going to happen next? And they need answers quickly because every day that passes, (quite understandably), increases their sense of frustration, trauma and mistrust.

Research on open disclosure, or being open1, as it is called in the UK, has shown that most patients, (quite rightly), expect an acknowledgement, a sincere apology, an explanation, support, information on what can be done to rectify physical harm and reassurance that the organisation involved will implement improvements to prevent another patient suffering the same trauma. Research has also identified a mismatch between patient expectations versus what doctors think patients want after medical errors occur.2,3

5 ASSUMPTIONS THAT PREVENT EMPATHETIC RESPONSES

Human beings are prone to making assumptions. In healthcare, the assumptions we make made about giving apologies and explanations need to be challenged if we want to improve patients’ and carers’ experiences. Five assumptions that detract from providing empathetic and effective responses when things go wrong are:

The skills assumption: All too often it is assumed that senior healthcare professionals have the skills to offer empathetic apologies. This is a myth. Many patients recount experiences of insincere or bureaucratically-worded apologies that were devoid of humanity. In the words of GK Chesterton, “A stiff apology is a second insult… The injured party does not want to be compensated because he has been wronged; he wants to be healed because he has been hurt.”

The policy assumption: Healthcare organisations sometimes take false assurance that having a local policy on apologies and explanations means that patients and carers will be supported appropriately following an incident. Although having a policy is desirable and should be encouraged, it is not in itself a fail-safe barrier. How many healthcare organisations routinely collect patient and carer experience on whether they received an empathetic apology and explanation after an incident? My guess is that the answer is ‘very few.’ Yet this is the acid test of how well local policies are working and the foundation for future improvement.

The perspective-taking assumption: When things go wrong we assume that healthcare professionals will immediately see things from the patient’s perspective. The sad reality is that distancing and denial kick in and render them unable to walk in the shoes of the patient.

The ‘I know what patients need to hear’ assumption: Healthcare professionals also make assumptions about what patients and carers want in the aftermath of an incident. These assumptions are often wrong. I remember debriefing one consultant who had been completely off-sided and humbled when a patient replied that the most important thing for her was reassurance that she could still be treated on the same ward where her medication incident occurred. The consultant had wrongly assumed she would want to be treated elsewhere. Her reply was a salutary lesson on the importance of not assuming we know what patients want.

The ‘we can plan for all eventualities’ assumption: Although it is important to know as much about the patient and carers, and about the nature of the incident as possible, you cannot plan how people will react to the information you provide. It is often difficult to anticipate how patients or carers will react to the information you share. Emotional reactions range from outbursts of anger, shock to calm acceptance or humaneness and forgiveness.

Many of the healthcare professionals I have mentored think they can plan for all eventualities, only to be taken by surprise by patient and carer reactions during a meeting. Pre-rehearsing a scripted apology will make you come across as a bureaucrat. It also closes off the patient or carer, making it difficult for them to ask the questions they most want answered.

To ensure patients and carers are better supported in the aftermath of an incident healthcare professionals need to be aware of their own human frailties. Be aware that distancing and denial are normal human reactions after an incident has occurred. And challenge the five assumptions that detract from our ability to offer patients and carers sincere apologies and honest explanations.

REFERENCES

National Patient Safety Agency. (2009). Being open framework. Communicating patient safety incidents with patients, their families and carers. Available at: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/collections/being-open/?entryid45=83726

Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003: 26;289(8):1001-7.

Iedema R, Allen S, Britton K, Piper D, Baker A, Grbich C, Allan A, Jones L, Tuckett A, Williams A, Manias E, Gallagher TH. Patients’ and family members’ views on how clinicians enact and how they should enact incident disclosure: the “100 patient stories” qualitative study.BMJ. 2011:25;343:d4423.

© Copyright Dr Jane Carthey. 2013

Posted on September 5, 2013 : 1:07 pm Comments (2)

Filed under news